Andrea Sealy - Meteorologist

Fitting new pieces into the African drought puzzle

Andrea Sealy, Ph.D., is a scientist at the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology. She spent two years as a postdoctoral fellow in NCAR's Advanced Study Program.

Photo courtesy Andrea Sealy.

If you are from the Caribbean and you're good at math and science, the advice you get is to become a doctor, says Andrea Sealy. "But I never liked biology much," she adds.

A great school teacher pointed her down what would eventually become her career path. "My geography teacher was really knowledgeable. I was fascinated learning about how weather works. I said to myself, this looks like fun, perhaps I can do this." That same year, a meteorologist at a school career day told Sealy that the field required a lot of math and physics—both subjects that she loved. "That was it. I was 14 or 15 at the time, and from then on, that was what I was going to do."

Dashing to college in the states

Her road to the United States started on the running track. In high school she was captain of the girl's track team, and she continued running when she entered college. "My coach said, Maybe we can get you to the U.S," she recalls. "One of the schools he was thinking of was Jackson State University, which has a meteorology major, so I didn't have to sacrifice my major to get a track scholarship."

Although she no longer runs, Sealy would like to coach someday. "I still really enjoy looking at athletes' technique and seeing where they could improve."

‘I said to myself, this looks like fun, perhaps I can do this.’

Running into unfamiliar territory

Gregory Jenkins recruited her for grad school when he was at Pennsylvania State University. "Coming from Jackson State, where she was an outstanding student, to Penn State where there are a lot of outstanding students, was a challenge," says Jenkins.

Sealy became Jenkins' research assistant. "Being with a great mentor like him gives you the enthusiasm to enjoy this stuff. So I started looking at West African climate for my master's work. Coming from the tropics myself, I've always been interested in tropical climate, and there's so much work that needs to be done in that area. It's a region where it would be good if scientists could contribute their knowledge to helping the people." The two studied rainfall processes using data from the TRMM (Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission) satellite. Sealy continued to Howard University and received a Ph.D. in 2006.

‘After being so well educated and having so many diverse experiences, it'll be good to see what I can contribute to the field at home.’

Expanding experiences

It was also Jenkins who encouraged Sealy to apply for a postdoctoral fellowship at NSF NCAR, which she completed in 2008. "She's a creative person, and to bring the best out of a creative person, they need an environment with growth potential. I thought from my own experience [as an NSF NCAR postdoc] that she would flourish out there, and that's what happened."

Throughout her education, Sealy took advantage of summer programs, internships, and any possible opportunity to stretch herself. One summer at the University of Oklahoma she participated in Earthstorm, a program that brings K-12 teachers to campus to learn basic meteorological principles. "I had always liked education and outreach, but that experience is what really fueled my interest, how as a scientist you can talk to others who are not in the field," she says. Since then she has been involved in a wide range of outreach endeavors.

Home again

After many years in the United States, Sealy is back in Barbados. She's now a researcher at the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology, part of the Caribbean Meteorological Organization.

"After being so well educated and having so many experiences, it'll be good to see what I can contribute to the field at home. My new director is of the mind set that even though you're coming back home, don't fall off the radar. So I'll be coming back for professional meetings and workshops, and I'll continue to collaborate."

Jenkins believes that Sealy's outgoing personality and positive attitude will inspire other young people to come into the field.

The drought detective

Andrea Sealy has been working for the last two years to find some answers to the many questions surrounding the Sahelian drought. Sealy received a Ph.D. from Howard University in 2006. Her thesis research applied computer modeling to studies of soil moisture and precipitation in Africa. As a postdoctoral fellow at NSF NCAR, she expanded to model interactions between dust and dynamic vegetation and how they affect precipitation—a scenario that comes a few steps closer to the complexity of the real world. Her investigative tool is the NSF NCAR Community Atmosphere Model.

Dust by proxy

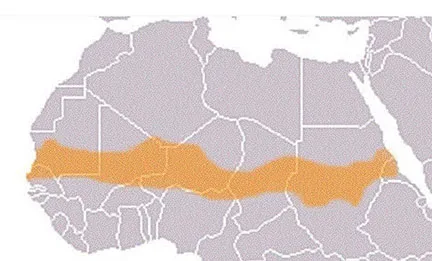

Sahel stretches across the midsection of northern Africa, from part of Senegal in the west to part of the Sudan in the east.

Image courtesy the GLOBE Program

One reason to study this problem with computer models is that there are no long-term dust observations from the African continent. But African dust wafts all the way across the Atlantic on the prevailing easterlies. Sealy used a data set on dust in Barbados, which is not only the most easterly Caribbean island but her native country. "People often refer to the Barbados observations if they want to get a sense of the seasonal cycle and how the dust has varied over time," she says. She did some model runs that included the radiative effects of dust and some that did not.

Should plants grow or stand still?

Another variable in the experiment was the treatment of vegetation: some runs used the model's default, which specifies fixed states for vegetation covering the land surface. Others used a dynamic vegetation treatment. "Dynamic vegetation is more of a natural way of looking at things," Sealy explains.

Plants change seasonally and also in response to climate changes; they spread with increased precipitation and die off during droughts. Species mature and are replaced over time. There are biogeochemical connections as well, such as vegetation's role in the carbon cycle.

Another suspect: Ocean warming

This graph reveals erratic swings in seasonal precipitation since 1900 for the five-month season from June through October in the African Sahel region. Note how many years show below-normal rainfall since the late 1960s.

Image courtesy Andrea Sealy and NOAA

The treatment of sea-surface temperatures was a third variable; Sealy used observed temperatures in some runs, while in others the SSTs were interactive, responding to changes in other parts of the model. SSTs are a major contributor to the drought, according to several scientists.

The engine powering African monsoon rains is the temperature difference between the ocean surface surrounding the continent and the land surface within. A warmer ocean means less temperature difference; as a result, moisture stays over the oceans, and Africa stays dry and dusty. So SSTs have an effect on dust, but dust also has an effect on SSTs, reducing incoming solar radiation over the oceans and keeping them cooler.

More realistic vegetation, more complex results

Sealy found that the dynamic vegetation treatment did affect both precipitation and dust in the model runs, reproducing reality better in such things as the timing of peak dust concentrations in Barbados. When she compared observed SSTs versus interactive ones, the effects on dust, precipitation, and dynamic vegetation also varied, in complex ways that are not yet clear.

She also compared the difference in dust during the dry period of the 1970s and 1980s in the Sahel and the most recent wetter period, in the 1950s and 1960s. With dynamic vegetation, "you see a bigger difference in dust from the wet period to the dry period," she explains. The reason for this is not completely understood, she says. "It could be that during the dry period you're getting more desert," and the greater expanse of exposed soil can become airborne more easily. "However, there are a number of other things that could be in play there, like changes in albedo and radiative forcing."

Sealy describes her work modestly as "another little piece in the age-old puzzle of what affects Sahel precipitation." Her postdoc adviser at NCAR, Natalie Mahowald (now at Cornell University), is less understated. "Her study was the first looking at these interactions in an integrative model, but it's not going to be the last. It's a very important study.”

October 2008

What advice would you offer to someone interested in a career like your own?

Step out of your comfort zone.

Andrea Sealy advises students to push their limits in pursuit of a science career.

And don't get discouraged, she adds. "Eventually, you raise your comfort zone to a different level. When I go back to Barbados I'm very comfortable, but I'm also fine here [in the United States]."