Christopher Castro - Assistant Professor

In pursuit of the Southwest's monsoon

Chris Castro is an assistant professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science, University of Arizona. Castro is a UCAR SOARS alumnus.

Photo courtesy University of Arizona

Christopher Castro is proof of the value of a summer internship. Castro always had what he calls a passing interest in weather. He liked to watch the summer storms roll in from the west as a boy in Oklahoma, and on a trip to Arizona as a teenager, the monsoon rains "just fascinated the hell out of me," he says. But he never thought of his hobby as a career path; he was going to be a lawyer.

Castro’s father was an animal diagnostic virologist, and his childhood was spent in a series of college towns with veterinary schools: Stillwater, Oklahoma; Davis, California; and State College, Pennsylvania. Castro chose Pennsylvania State University largely because, with his dad on the faculty, his costs were low. He enrolled as a pre-law major in 1993.

A bend in the road

After his freshman year, his life took a different turn. He spent that summer at an internship in the civil rights office of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. "After working there, I couldn’t see myself in that profession. I did enjoy the people aspect, but law was not compatible with my personality."

Now Castro needed a new career path, but he still wanted one that was relevant to the problems of today’s world. "I thought, why not do something that you’ve always had a passing interest in and that still has a connection to society?" He switched his major to meteorology, a decision he now compares to "jumping into a pool without knowing how deep it is. It was risky—very risky."

A year into his new major, he had a very different kind of summer internship: NSF Significant Opportunities in Atmospheric Research and Science program, then in its second year. NSF SOARS gives college students the experience of life as a scientist. Each student, known as a protégé, comes to NSF NCAR or another participating lab for research projects over the course of three summers, with intensive mentorship guiding the protégé toward graduate school and a science career.

Choosing a home

When he completed his Ph.D. in 2005, Castro says, "I had the opportunity of several jobs, including coming back to NSF NCAR. I decided to come here [to Arizona]; I felt like this was where I was most needed. I had the opportunity to be the captain of the ship and to shape the ideas of my students instead of being in a big group and having someone tell me what to do. That’s the riskier path, but it’s more rewarding in the end.

About the Research

Toward the end of June in the U.S. Southwest, many people begin to watch the skies in the afternoon. They’re eagerly awaiting the first rains of the summer monsoon season, a period of several months that brings much-needed moisture and relief from the scorching heat of the early summer.

When he first saw those spectacular thunderclouds and torrential rains in Ajo, Arizona, Christopher Castro was a 15-year-old from Davis, California, who intended to be a lawyer when he grew up. Now he’s a professor in the University of Arizona's Atmospheric Science Department, and he’s working to forecast the summer downpours.

"The monsoon phenomenon directly affects about 20 million people in all sorts of ways—agriculture, wildfires, you name it," Castro says. "If you can come up with a better way to forecast the monsoon, that is of significant interest."

A very wet season

The monsoon season accounts for a significant portion of the year’s precipitation in northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, averaging from over 2.5 inches in Phoenix—more than a third of the annual total—to almost 52 inches in Acapulco, about 95% of that city’s yearly rainfall. The dark side of all this water is millions of dollars per year of property damage and sometimes deaths from flooding, especially if the rains are fueled by a tropical storm in the eastern Pacific.

Although most of us immediately think of rain when we hear the word monsoon, the term actually means a seasonal shift in winds. In North America, the prevailing winds from the west or north change to southerly and southeasterly. These flows carry moisture inland from the Pacific Ocean, Gulf of California, and Gulf of Mexico. The complex topography of the region means that rainfall is not uniformly distributed, even at the same latitude; mountainous terrain tends to receive the lion’s share, while some unlucky places like Yuma, Arizona, traditionally stay parched.

From computer models to field campaigns

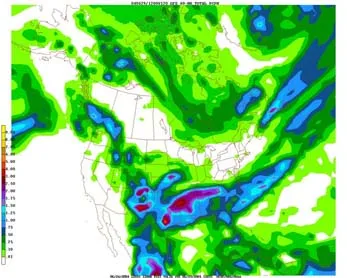

This 120-hour precipitation outlook for June 24-29, 2004, including 60-hour precipitation totals, was issued during the North American Monsoon Experiment. The NAME forecast showed strong rainfall potential developing in New Mexico and called for a new backdoor cold front to move into central and southern New Mexico after 24 hours. The 5-day forecast indicated rainfall would exceed 2 to 3 inches in sections of south-central New Mexico.

Image courtesy NOAA

While he was in graduate school at Colorado State University, Castro used computer modeling to study the effects of Pacific sea surface temperatures on the North American monsoon. He and his colleagues found that cold sea-surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific typically correlate with an early monsoon and heavy rains in the southwestern United States and dry, hot weather in the Great Plains. Warmer sea-surface temperatures, such as are found in El Niño years, tend to have the opposite effect. The article reporting their findings is available online from the Journal of Climate.

Castro got a look at the Mexican side of the monsoon in 2004, when he took part in the field campaign of the North American Monsoon Experiment, or NAME, as a rawinsonde (weather balloon instrument) operator in Mochis, Mexico. His bilingual skills were also put to use as a site translator.

NAME, sponsored by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Mexico’s weather service, collected data in both countries and over the Pacific with the goal of improving monsoon forecasting. Castro has since been appointed to the NAME Science Working Group.

When Castro completed his Ph.D. in 2005, he chose the University of Arizona because of his interest in the local climate, and also as a place where his bilingual ability would be useful.

Monsoon forecasting makes news

In June 2007, Castro’s prediction of an early monsoon season with heavy rains got him on the front page of Phoenix’s newspaper, the Arizona Republic.

This prediction wasn’t only based on observations of cool sea-surface temperatures. Castro explains, "In the Southwest, the winter behaves in a totally opposite way than the summer does, so when we have a dry winter it’s typically followed by a wet summer." Arizona had an extremely dry winter in 2006–07, continuing a string of some of the driest winters on record.

How did the season play out? "Aside from the fact that the onset date was normal to a bit delayed, everything else that has happened this summer pretty much fits this pattern," Castro says. "It has been wet in the Southwest and dry and hot in the Dakotas and eastern Montana, with temperatures regularly topping one hundred degrees [Fahrenheit] there in August."

The path toward better prediction

Along with his teaching duties, Castro has been putting out proposals to continue his research in several directions. Following up on his graduate school computer modeling, he would like to do retrospective simulations of the NAME field campaign year to address questions about the physical mechanisms of rainfall and help in the design of a long-term observing system in the United States and Mexico.

Another proposal is to develop a useful regional version of the seasonal forecasts from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction’s global model, a process known as downscaling. "If you look, for example, at the maps of the warm season three months out, there’s virtually no skill, particularly for precipitation," he says. "I believe that a regional model will better represent the processes that lead to summer rainfall."

When the rains don't come: Planning for future drought

Chris Castro talks about interacting with students and about his research.

Several years of drought in the U.S. Southwest have decision makers across the region concerned about future water resources. To help Arizona plan for that future, Castro is leading an investigation into the region's climate past. Besides examining records of precipitation and temperature, the project will seek out the local history of agricultural water users and other stakeholders in order to build what he calls customized drought indices.

The goal is to improve the way drought is reported and provide information useful to decision makers. "The unique thing about this focus is that we'll analyze different time scales of drought, which is important depending on who you are," Castro said in a recent University of Arizona report.

November 2007

What advice would you offer to someone interested in a career like your own?

Ask people what they actually do.

"Go and talk to people working in the field, figure out what they do," says Chris Castro. Any career requires more than just the ability to do the work. "It’s important to find not only something that you can click with in terms of your profession but a community that you feel comfortable with socially. The only way you get a sense of that is by going and talking with people."

And don’t be afraid to take risks. "Sometimes you’re going to fail, but you’ll learn from your failures and grow more than if you always take the safe path. Your life may have more ups and downs. but it will be more rewarding in the end. That’s what defines successful people."