Cory Morse - Software Engineer

Engineering software for safer skies

Cory Morse

Carlye Calvin, UCAR

Working at NCAR for nearly two decades has taught Cory Morse that she has the soul of an engineer.

"There's always been a creative tension between scientists and engineers, with scientists wanting to understand the world and engineers wanting to build things that work," Cory says. "They're both useful approaches but they're different, and I realize that I'm clearly on the engineering side of the divide."

Cory, whose education and background are in science, has found a perfect niche working as a software engineer in NCAR's Research Applications Laboratory. "I don't think that if I had tried to design a job for myself I could have done any better," she says.

Out of the JAWS of turbulence

For the past ten years, Cory has helped design and refine the Juneau Airport Wind System (JAWS), a real-time turbulence warning system for planes flying in and out of Alaska's capital. The Juneau airport, which is surrounded by mountains, is notorious for testing pilots and rattling passengers. The steep, dramatic peaks lining the runway not only restrict flight paths but also create complex wind-flow patterns. Before aircraft adopted GPS technology, a pilot departing Juneau sometimes had to make a precise 180-degree turn, often in the face of intense winds, inside a narrow airspace.

"If you get hit with turbulence, you don't have a whole lot of room to maneuver because of the mountains," Cory says.

In the early 1990s, turbulent winds resulted in several close calls, which caught the attention of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). In 1998, NCAR teamed up with the FAA to better predict turbulence at the airport.

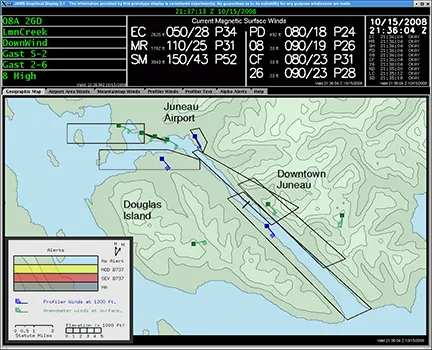

A data display for the prototype Juneau Airport Wind System shows current wind conditions and the airport's alert areas.

NCAR Research Applications Laboratory

A team of NCAR researchers that included Cory began by collecting raw data near the airport, using wind profilers (upward-pointing radars) and mountain-top anemometers that measure wind speed and direction. They also conducted test flights with research aircraft. "It was funny to see the scientists who flew through turbulence come back looking green," Cory recalls.

Using algorithms (mathematical formulas) they designed to analyze the data, the team then developed software that takes these measurements and issues up-to-the-minute alerts about turbulence to air traffic controller specialists, airline dispatchers, and pilots. A JAWS prototype is currently in place in Juneau, and the team expects to deliver the final product to the FAA in the next few years.

Cory has been the primary software architect for the project, writing the infrastructure that lets the researchers "plug and play" their algorithms. "I'm really proud of it because we've built a nice framework for real-time systems that lets us reuse our code and put it in different contexts," she says. "It's been really neat to go out in the field to see how it will be used and know it's enhancing safety."

From blank page to U.S. patents

Cory's efforts on the Juneau project are based on similar work that NCAR did for Hong Kong International Airport. Situated on the edge of mountainous Lantau Island, regular thunderstorms and high winds make turbulence and wind shear a certainty at this airport. To develop the severe weather warning system that NCAR designed for Hong Kong in the mid-90s, the software team started with a blank page and wrote all code from the ground up.

"I learned a lot during that project," Cory says. "We built on it for Juneau, refining the architecture started in Hong Kong. It took a long time to develop the concept and design, but now it's fully realized and that's exciting to me," she says.

The Hong Kong project led to another important development. Cory was working with colleague Larry Cornman to use wind profilers at the airport when they realized that the instruments had significant quality control issues as the data were averaged over a few minutes rather than a half hour or more. After Larry conceptualized an algorithm to obtain more reliable data from the profilers, Cory implemented it in software. The result was the NCAR Improved Moments Algorithm, which garnered two patents.

To collect data for the Juneau Airport Wind System, researchers measured turbulence with a research aircraft from the University of Wyoming (left) and an Alaska Airlines commercial aircraft (right) in 2002.

David Albo, NCAR

Variety's the spice of work

One of Cory's favorite things about her job is that she gets to work with "top-notch people." She also appreciates getting to do a variety of tasks; in addition to software engineering, she's also dabbled in data analysis and algorithm development. "Almost any of the things that I like to do I get burnt out on if I do continuously, so it's nice to change and do something different," she says.

One of the biggest challenges that Cory experiences is people management. "I'm kind of a technical nerd who's pretty happy sitting at the computer banging out code," she laughs. "Trying to organize people to get a job done is a hard task, so I have a lot of admiration for managers who do it well."

Helping ideas become reality

Cory grew up in Tucson, Arizona. In school, she was drawn to math and science. Following in the footsteps of her father, a pharmacist, and her grandfather, a chemist, she chose chemistry as her major at Harvey Mudd College. She began graduate work in organic chemistry at the California Institute of Technology, but found herself stymied with uncertainties about her career path.

"It wasn't quite clear to me what I was going to do job-wise with a chemistry degree once I got out," Cory says. She quit school and got a job in systems engineering at one of southern California's aerospace companies, where she learned that she liked developing software and algorithms.

In 1990, Cory landed her NCAR job, a position that she says suits her personality very well. "I'm very much a support-type person who likes to help make good ideas a reality," she says. "It's good for me that science leads the show at NCAR and engineering is in a support role."

Cory advises that software engineers who aspire to work in research settings be grounded in math and science. "These are the things you'll be implementing and thinking about, so having that background is really helpful," she says.

She also advises to keep an open mind. "You sometimes get on track with what you think you're going to do in school or your career, but there are always more options than anybody ever tells you about. You have to look around because nobody is going to tell you what they are."

by Nicole Gordon

November 2008