Hector Socas-Navarro - Astrophysicist

Focusing on the Sun's magnetic field

Hector Socas-Navarro

Carlye Calvin, UCAR

When Hector Socas-Navarro was 10 years old, he watched Cosmos, Carl Sagan's famous television series about the universe and our place in it. It was then that he decided to become a scientist.

"Sagan had the ability to make things easy to understand but at the same time show the mystery that's out there waiting to be explored," Hector says.

Today, Hector's job is to explore these very mysteries. An astrophysicist in NCAR's High Altitude Observatory, he studies the most prominent feature in our solar system, the star that makes life on Earth possible—the Sun.

"The Sun is a very interesting star because it's closest to us, so we can study it in a lot of detail, which we can't do with other stars," he explains.

Hector's main interest is the Sun's magnetic field. Magnetism is the key to understanding the Sun, for it drives solar activity and produces most of the Sun's features, including the solar storms that buffet Earth's atmosphere. Magnetism is produced by the flow of electrically charged ions and electrons from the Sun.

In particular, Hector focuses on the chromosphere, the layer just above the photosphere, which is the part of the Sun visible to the human eye. "It's an extremely interesting layer where things are going on that we don't quite understand," he says.

He looks at data from the chromosphere to better understand the interactions between magnetic fields and plasma (electrically charged gas). While studying for his doctoral degree, he developed a new technique to analyze these interactions that infers the height distribution in the chromosphere of variables such as temperature, velocity, density, and magnetic field.

Learning more about the Sun's magnetic fields is important because solar storms affect Earth. Known as coronal mass ejections, these outbursts of energy from the Sun send billions of tons of matter and charged particles hurling through space, throwing off satellites, ground-based communications systems, and power grids on Earth.

"This has a direct impact on society as we rely more and more on technology, such as satellites and GPS," Hector points out.

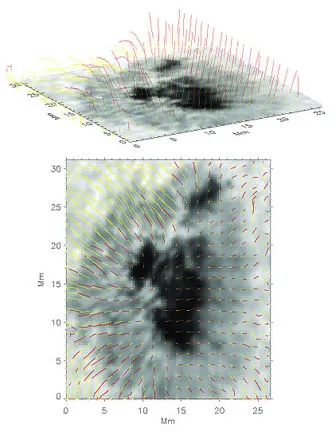

Hector developed a technique to convert data from an instrument called SPINOR (Spectro-Polarimeter for Infrared and Optical Regions) into this representation, which is the first portrait of the Sun's three-dimensional magnetic field to be created from observations. The magnetic field reaches to about 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) in height. The yellow segments represent the magnetic field lines from the Sun's surface up to a height of 500 km (310 mi) in the photosphere. The red segments represent the same field lines from 500 to 1,500 km in the chromosphere.

Illustration courtesy Hector Socas-Navarro, NCAR

In addition, by studying the Sun's various phenomena, such as solar storms, solar flares, and sunspots, Hector and other astrophysicists can also learn more about other stars.

"These phenomena aren't specific to the Sun, but also take place on other stars, in some cases much more violently than on the Sun," Hector says. "I'm exploring what we can learn from applying techniques from solar physics to other scenarios."

One of Hector's current projects involves working on the solar oxygen abundance question. In recent years, there's been indication that some measurements of the Sun's chemical elements that scientists thought were well-established—oxygen in particular—could be wrong by as much as a factor of two.

"There's a lot of controversy, as some people think we should revise the oxygen abundance and adopt the new lower values, while others claim that the new values are wrong and we should stick to the previous ones," Hector says.

He's also collaborating with scientists and engineers from across the solar physics community to design instrumentation for the Advanced Technology Solar Telescope, which has been described as the world's greatest advance in ground-based solar telescope capabilities since Galileo. Slated to begin operating in the next four to five years, the telescope will be situated at about 10,000 feet in elevation atop Haleakala on the Hawaiian island of Maui.

"I typically have several projects going at once, so if I get stuck on something I can work on something else," Hector says.

This freedom is one of his favorite things about his job. "The nice thing about my position is that when I'm frustrated or bored it's easy for me to find something else to do," he says. "Another thing I really like is that it's a constant learning process. I'm learning new things every day from what I read and conversations with colleagues."

Hector aspires to use his solar expertise to branch out into other fields in astrophysics. In particular, he'd like to take a close look at the magnetic fields of other stars. "With all we've learned about the Sun, I think the next natural step is to apply those things to other stars, and also use other stars as a laboratory to learn about processes going on in the Sun," he says.

He considers himself very fortunate to be working in astrophysics. "This is what I always wanted to do since I was a kid," he says. "If I were a wealthy person and had the means to not work at all, I think I would still come here every day."

Hector grew up in the Canary Islands, an autonomous region of Spain off the coast of Morocco. His parents nurtured his interest in science by emphasizing the importance of education in general, and even bought him the book version of Cosmos after he was so impressed by the television series. Living in the Canary Islands was a stroke of good luck, as the islands boast world-class telescopes and observing facilities, such as those at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canaries (IAC).

"The astrophysics school is very strong, so I had the means to get an education in the field and didn't have to think about going abroad," Hector says. After earning a Ph.D. at the University of La Laguna, he came to HAO, where he's been since 1999.

He warns that being a scientist is not necessarily an easy path, though. It's a very competitive field, and one that often requires personal sacrifices.

"You're expected to move around a lot, maybe from one country to another, and often it's very difficult to make that compatible with family life," he says. "I've been lucky in that I've landed in a nice place and have been able to maintain stability."

Despite the challenges, the opportunity to satisfy one's curiosity as part of a job is worth it. "To be able to be involved in cutting-edge research is very rewarding," Hector says. "You work on a problem and you don't know what you're going to get—is it going to confirm what you think, or crush your theory?"

He encourages young scientists to brace themselves for hard work and sacrifices, but to expect great satisfaction as well. "The skills you will develop, the people you will meet, and the joy of doing something you want to do is a wonderful experience."

by Nicole Gordon

September 2007

Update: Hector Socas-Navarro is now on the research staff of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain (April 2010).