The Stratosphere

The stratosphere is a layer of Earth's atmosphere. It is the second layer of the atmosphere as you go upward. The troposphere, the lowest layer, is right below the stratosphere. The next higher layer above the stratosphere is the mesosphere.

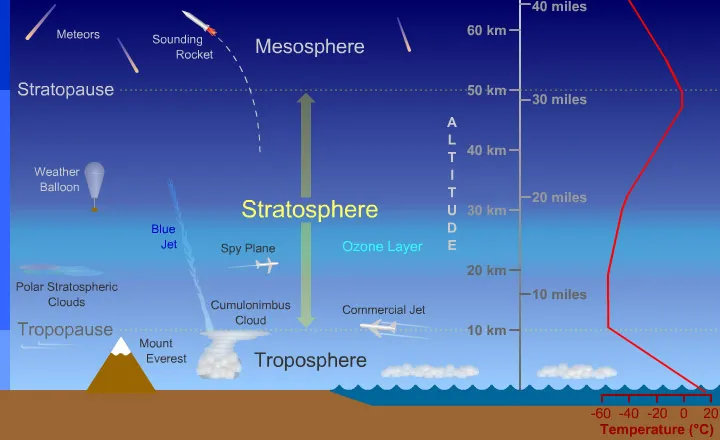

This diagram shows some of the features of the stratosphere.

UCAR/Randy Russell

The bottom of the stratosphere is around 10 km (6.2 miles or about 33,000 feet) above the ground at middle latitudes. The top of the stratosphere occurs at an altitude of 50 km (31 miles). The height of the bottom of the stratosphere varies with latitude and with the seasons. The lower boundary of the stratosphere can be as high as 20 km (12 miles or 65,000 feet) near the equator and as low as 7 km (4 miles or 23,000 feet) at the poles in winter. The lower boundary of the stratosphere is called the tropopause; the upper boundary is called the stratopause.

Ozone, a type of oxygen molecule that is relatively abundant in the stratosphere, heats this layer as it absorbs energy from incoming ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. Temperatures rise as one moves upward through the stratosphere. This is exactly the opposite of the behavior in the troposphere in which we live, where temperatures drop with increasing altitude. Because of this temperature stratification, there is little convection and mixing in the stratosphere, so the layers of air there are quite stable. Commercial jet aircraft fly in the lower stratosphere to avoid turbulence and increased atmospheric drag, which are common in the troposphere below. Air is roughly a thousand times thinner at the top of the stratosphere than it is at sea level.

The stratosphere is very dry air, containing little water vapor. Because of this, few clouds are found in this layer. Polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) are the exception. PSCs (also called nacreous clouds) appear in the lower stratosphere near the poles in winter. Made of ice, they are found at altitudes of 15 to 25 km (9.3 to 15.5 miles) and form only when temperatures at those heights dip below -78° C. They appear to help cause the formation of the infamous holes in the ozone layer by "encouraging" certain chemical reactions that destroy ozone.

Due to the lack of vertical convection in the stratosphere, materials that get into the stratosphere can stay there for long times. Such is the case for ozone-destroying chemicals called CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons). Large volcanic eruptions and major meteorite impacts can fling aerosol particles up into the stratosphere where they may linger for months or years, sometimes altering Earth's global climate. Rocket launches inject exhaust gases into the stratosphere, producing uncertain consequences.

Various types of waves and tides in the atmosphere influence the stratosphere. Some of these waves and tides carry energy from the troposphere upward into the stratosphere, others convey energy from the stratosphere up into the mesosphere. The waves and tides influence the flows of air in the stratosphere and can also cause regional heating of this layer of the atmosphere.

A rare type of electrical discharge, somewhat akin to lightning, occurs in the stratosphere. These "blue jets" appear above thunderstorms, and extend from the bottom of the stratosphere up to altitudes of 40 or 50 km (25 to 31 miles).

Updated and adapted from previous content from Windows to the Universe (original material © 2009 NESTA)