Shifting Ecosystems

More than 89% of the changes that we have seen in ecosystems today are consistent with a response to climate change. This is according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Climate change is just one of the many reasons that ecosystems on land are changing. These changes are happening for many reasons related to how humans utilize natural resources and develop the land, as well as pollution and strategies for wildlife management.

To assess how much of the change in ecosystems was potentially due to climate change, the panel looked at the studies that had been done about ecosystems in the 20th Century and compared the changes that were documented to the types of changes that would be expected due to climate change.

Expected changes in ecosystems due to climate change usually fall into two categories. Ecosystems may change geographically, moving into areas that had previously been too cold and dying out in areas that have become too hot. Ecosystems may also change the timing of seasonal cycles as warm temperatures arrive earlier in the spring and leave later in the autumn.

Geographical Changes in Ecosystems

Following shifting temperatures, many species of animals and plants have shifted their geographic ranges poleward (to the north in the Northern Hemisphere and to the south in the Southern Hemisphere). Also, as higher elevations experience more mild winters, for example, species from lower elevations may expand their range towards higher elevations because they can now tolerate the winters there. These “range expansions” can be advantageous for species that can disperse easily, but they can threaten the existence of less mobile or more sensitive species. They can also lead to ecosystem mismatches in which a species moves into a new area and no longer has its usual food sources or faces different predators.

Migration into new territory is often impossible, as habitat fragmentation due to human activities (such as the building of housing developments, golf courses, highways, or shopping malls) or the existence of natural barriers such as rivers or mountain ranges can prevent the movement of animals or dispersal of seeds and fruits.

As the Arctic has warmed, trees are moving into areas that had previously been too cold and frozen to support trees.

INSTAAR, University of Colorado, Boulder

Timing Changes in Ecosystems

For plants and animals with yearly cycles (phenological cycles) that are linked to changes in temperature, climate warming can mean that phases of their cycles are triggered earlier in the spring and later in the fall. For example, flowers may bloom earlier in the spring if temperatures allow and leaves may turn colors and drop later in the autumn.

There are thousands of records of seasonal changes in plants and animals that indicate shifts in timing through the 20th Century. Mammals and insects are emerging from dormancy earlier. Birds, insects, and mammals are changing the timing of their migrations. Plants are developing new leaves and stems earlier in the spring and shedding their leaves later in the fall, and many species are breeding earlier.

In the Northern Hemisphere, spring temperatures have been arriving over one day earlier each decade. The land holds onto more heat during the summer, allowing warm temperatures to linger into autumn. This means expanding the growing season in areas where plants receive enough rainfall to support additional growth. In Europe, for example, the growing season expanded 10.8 days from 1960-1999. Six days were added due to warmer and earlier spring, 4.8 days were added due to summer warmth persisting into autumn.

An increase in the growing season in the Northern Hemisphere might be a positive change for farmers in high latitudes, but there are downsides as well. For example, a tree growing leaves several days earlier each spring may get a head start on its annual growth, but it also may be particularly vulnerable to leaf-eating insects (e.g., moth and butterfly larvae, leaf miners, and leaf-cutting ants).

The interconnections between species — for food, pollination, or seed dispersal — may be disrupted as some species change their timing and others do not. For example, if a plant species of plant produces flowers five days earlier in the spring, but its pollinators haven't arrived, then the numbers of plants or pollinators (or both) might decline. On the other hand, if a plant flowers early enough to “escape” one or more of its “natural enemies” (e.g., flower bud-eating beetle larvae), it may benefit from high flower and fruit production. The more specialized the relationship between species, the more vulnerable each of them is likely to be to changes in seasonal timing.

Animals that migrate between different ecosystems or biomes to complete portions of their life cycles (e.g., growth and sexual maturation vs. breeding) are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change because they have more interactions with other species, which may be disrupted. We've learned from radio-tracking and bird-banding efforts that birds are returning to spring and summer breeding grounds earlier and earlier, but the effects of these altered migration patterns on both the birds and the species with which they interact (as predators or as seed dispersers) are still an area of active research. As an example, long-term studies in Alaska show that eagles are, on average, starting their northward migration about half a day earlier each year – over 25 years, this small-seeming shift has added up to a change of nearly two weeks.

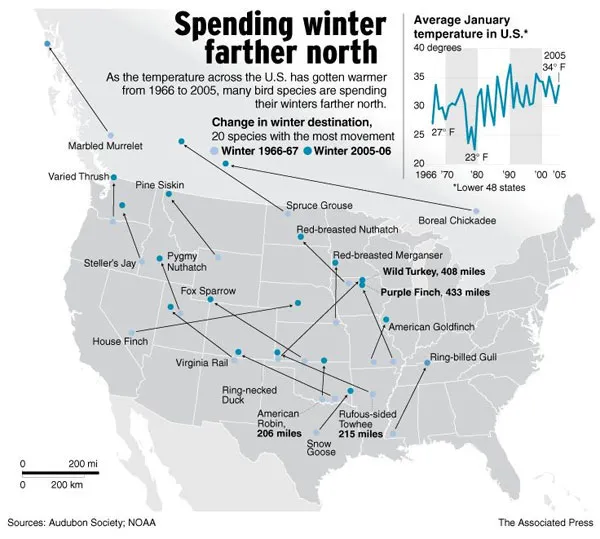

As temperatures have warmed, many bird species are spending winter farther north.

Audubon Society, NOAA, Associated Press

Multiple Effects on Animal Habitats

Habitats around the world are beginning to shift, shrink, melt and even disappear entirely as a result of climate change. Warmer temperatures associated with climate change are already affecting vegetation and food and water access for animals. To make things even worse, intense storms can damage or destroy nesting trees, drown animals, spread invasive species and harm aquatic ecosystems. Species affected by climate-caused habitat changes around the world include snow leopards, tigers, cheetahs, giant pandas, green sea turtles, monarch butterflies, African and Asian elephants, mountain gorillas, and corals and the aquatic life who depend on them.

In the Arctic, the effects are especially noticeable. Melting Arctic ice decreases the hunting areas accessible to polar bears. By 2100, polar bears across large areas on the Arctic could face starvation and extreme population declines. Changes in sea ice thickness can also negatively affect narwhals and walrus. Reindeer herds are also already declining, due in part to extreme snowfall and rain-on-snow events. In these events, the rain falls on snow and freezes, creating an unbreakable layer of ice that prevents the animals from getting to their food.

Oftentimes, the only way for species to survive is to travel, if there are more suitable conditions somewhere they can move to. Scientists are investigating how black bears, grizzly bears, caribou, moose, and wolves are affected by higher temperatures and increased rain or snowfall. They’ve found that moose and wolves move less in winters with higher snowfalls, and that predator species seem to respond to changing conditions differently than prey species. This difference can cause a mismatch between predators and the prey they hunt for food.

Resources to Explore: