Studying Lions from Space as Climate Changes

This mountain lion in Utah is wearing a tracking collar. The collar reports her location, which allows researchers to learn what amount of land she roams.

David Stoner, Utah State University

The American Southwest is becoming more prone to drought as Earth warms. How will the drier conditions affect mountain lions, the biggest cats in the United States? To find out, Utah State University ecologist David Stoner worked with remote sensing experts from the University of Maryland and other ecologists. They looked at the Southwest from space using an instrument on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites.

No, you can’t see mountain lions from space, but you can see plants.

The researchers looked at measurements of primary productivity - the amount of photosynthesis happening - with a satellite instrument called MODIS (moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer). Since plants do photosynthesis when they are alive and growing, the data indicate how much vegetation is on the ground.

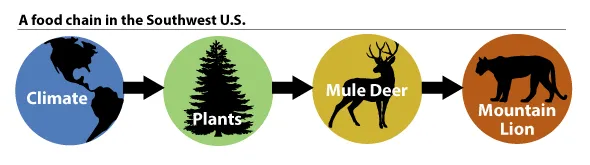

Those plants are connected to animals in food chains. In a typical Southwest U.S. food chain, plants are eaten by mule deer, which are eaten by mountain lions. So looking at the amount of plant growth visible in the satellite data and estimates of animal abundance on the ground can indicate how many deer are out there eating those plants and how many mountain lions are eating the deer.

The plants depend on the climate. They need water and sunshine. In the Southwest there is no shortage of sunshine, but water can be scarce, especially in times of drought – years when there is less rain and snow than usual.

Usually food chains begin with plants or other primary producers, but food chains also depend on climate. In the Southwest U.S., the amount of moisture in the environment affects the plants. Mule deer, herbivores, rely on a diet of plants. And mule deer are an important part of a mountain lion's carnivorous diet.

L.S. Gardiner/UCAR

Researchers compared the vegetation data from the satellites with data from several ecologists* about where mountain lions roam through the Southwest. The data were collected using special collars that keep track of the lions’ locations.

Mountain lions are top predators with large teeth and claws designed to harm, so getting one of these animals into a tracking collar takes some expertise. First, the ecologists look for tracks in fresh snow, which hold the lion’s scent. Then they release hounds, dogs trained to follow scent of cats. Hounds can outrun a mountain lion, and they do. By the time the researchers catch up, they find the dogs barking at the lion, which has climbed up a tree or is hiding in a pile of rocks. Using a dart gun, the researchers tranquilize the mountain lion. It later wakes up wearing a collar, which periodically reports its location back to the ecologists. (Note: Don’t try this at home.)

According to the scientists' results, mountain lions living in dry conditions, like a site near Las Vegas, roam a larger area than mountain lions living in more moist conditions, like the site south of the Great Salt Lake. An area with less water has fewer plants and less mule deer, so each mountain lion has to wander further to get enough food to eat. An area with more water has more plants and deer, so mountain lions do not have to go as far to find food.

Thus, the primary productivity measurements from the satellites can be used to estimate how many mountain lions live in an area. As drought becomes more common in the Southwest, watching the region’s plants from satellites can let wildlife managers know how many mountain lions are out there and how far they are likely to roam.

* Kirsten Ironside of the USGS Southwest Science Center and Northern Arizona University collected the mountain lion data from the Colorado Plateau. Kathy Longshore of the USGS and David Choate at University of Nevada collected mountain lion data from the Desert National Wildlife Refuge near Las Vegas. Mountain lion data from central and northern Utah were collected by David Stoner from Utah State University and Tom Edwards of the USGS Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. Heather Bernales of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources provided all the deer data.

Delve Deeper:

- What satellites can tell us about how animals will fare in a changing climate (NASA)

- How Climate Works

- Evidence of Warming

- The Impacts of Climate Change

Teachers:

- Try Project Wild’s Oh Deer activity with students to explore how the resources in the environment affect wildlife populations.

-

Help students understand food chains with the