Climate Influences on Severe Storms

A severe storm produces not just lightning, but additional dangerous conditions or hazards, including hail, particularly intense rain, or strong winds. You might have seen or heard news stories or anecdotal evidence linking current severe storms to climate change. But what does the science say? To understand how climate influences severe storms, let’s consider the key ingredients needed to form a thunderstorm. These include surface temperatures, temperatures higher in the troposphere and humidity.

Thunderstorms form and grow depending on the presence of specific ingredients, including enough water vapor or humidity as well as a difference between the surface temperature and temperatures higher in the atmosphere.

NOAA

Atmospheric Temperature as a Storm Ingredient

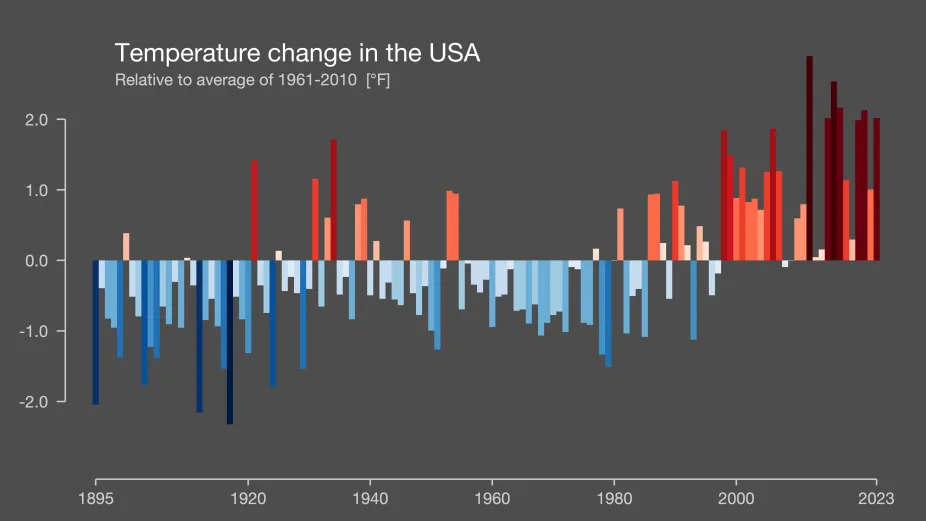

Average temperatures for the planet are increasing. But things aren’t warming at the same pace at every location. The U.S. is warming faster than the global average, experiencing recent yearly temperatures more than 1.1°C (2°F) above the 1961-2010 average. Looking back to 1895, the largest warming has occurred in the years since 1970.

Temperature departures from the 1961-2010 average, from 1895 to 2023. The red colors correspond to years with temperatures higher than the average, while the blue colors represent years with temperatures below the 1961-2010 average. The darkest colors represent the largest departures from the 1961-2010 average.

Creative Commons University of Reading

Scientists studying thunderstorm ingredients have found that storms are more likely to form in a warmer environment, as long as other atmospheric conditions are met. Warmer air near Earth’s surface helps create the upward motion, or convection, that can cause storms to form and grow. The warming already being observed due to climate change provides the background conditions for a greater chance of convection and potential severe storms.

Humidity as a Storm Ingredient

Warmer air can help water evaporate from Earth’s surface, increasing the amount of water vapor available in the atmosphere. For every 1.1°C (2°F) of warming, approximately 8% more water vapor can be present in the atmosphere. This water vapor helps fuel the development of storms, leading to more potential rainfall. Thinking about the average warming already observed, this means in many situations the atmosphere is already “juiced,” having ample water vapor available to foster and grow larger or more dangerous storms.

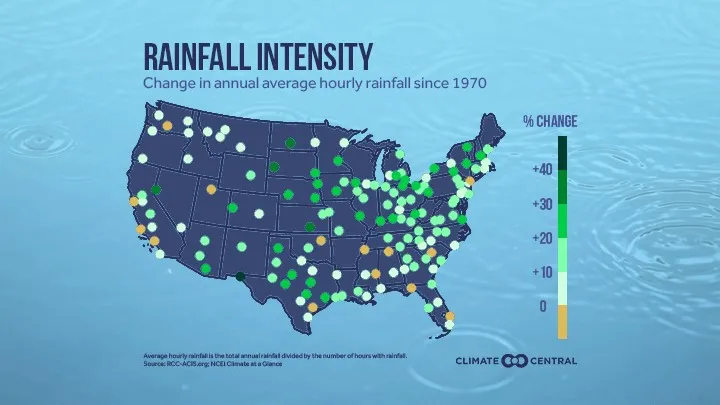

But more water vapor in the atmosphere doesn’t necessarily mean that all places will experience more rain, or that every storm will be more severe. Storms require specific atmospheric conditions in order to develop, grow, and produce rain. Only when the right combinations of conditions are present will the result be a thunderstorm that dumps more rain than normally occurs. Still, analysis of changes in rainfall finds some clear trends, with hourly rainfall intensities increasing an average of 13%, and up to 40%, across multiple U.S. locations since 1970.

The vast majority of U.S. locations analyzed — 136 of 150 — showed an increase in average hourly rainfall intensity between 1970 and 2022.

Climate Central

More Intense Storms, More Potential Hazards

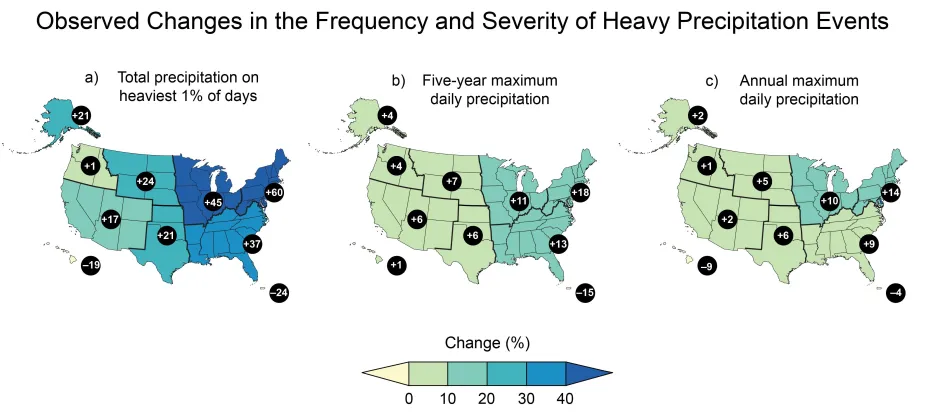

As the climate warms, extreme precipitation events can become more frequent and in some cases more severe. Rainfall from the heaviest storms has intensified across most of the U.S. from 1958 to 2021. The changes are most notable in the Northeast, which has experienced a 60% increase in its heaviest rainfall amounts, and the Midwest, where the amount of precipitation on the heaviest 1% of days has increased by 45%.

The heaviest (or most intense) downpours are becoming even heavier. Between 1958 and 2021, the total rainfall that occurred on the heaviest 1% of days, and the five-year and annual maximum daily precipitation, increased in almost all regions of the country.

USGCRP, 2023: Fifth National Climate Assessment. Crimmins, A.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023

These extreme downpours increase the risk of flash flooding, and scientists have documented that flash flooding worldwide was 20 times more frequent from 2000-2022 than from 1900-1999.

Severe storm events can be extremely damaging, bringing tornadoes, heavy rainfall, hail, or strong winds.

Top left: NOAA; top right: Creative Commons Tom Harpel; bottom left: John T. Allen; bottom right: istock

Other hazards from severe storms include lightning, wind, large hail, and tornadoes. In the 1980s, the U.S. experienced an average of three billion-dollar weather/climate events (natural disasters that cause at least one billion dollars worth of damage) per year. In 2024, there were 27 billion-dollar events, including 17 severe storm events involving tornadoes, hail, or straight-line winds.